The career-defining skills you can only learn in person

The postcard from the future I never wrote

Back in 2007 I didn’t recognise I was learning the most important skills of my career, and now I’m watching people miss them without understanding what they’re losing.

At the consultancy, we held a conch to speak in stand-ups. We rang a bell when we completed a story. We put a pound in a jar if we touched the mouse instead of using keyboard shortcuts. We wrote postcards from our future selves.

I participated in these experiments, but over time they grated. I was just there to write code, and all this ceremony felt like it was getting in the way of what I’d actually been hired to do.

When I left, I felt relief, finally free from people who’d drunk the Kool-Aid. In one of my least fine moments, I even mocked it publicly on Twitter, using a hashtag to call out what I saw as #AgileBS.

I thought I’d escaped something pointless, ready to focus on what mattered. Getting sh*t done.

In the years since, our success has depended on the practices I’d dismissed.

More than once.

And now, they are more important than ever.

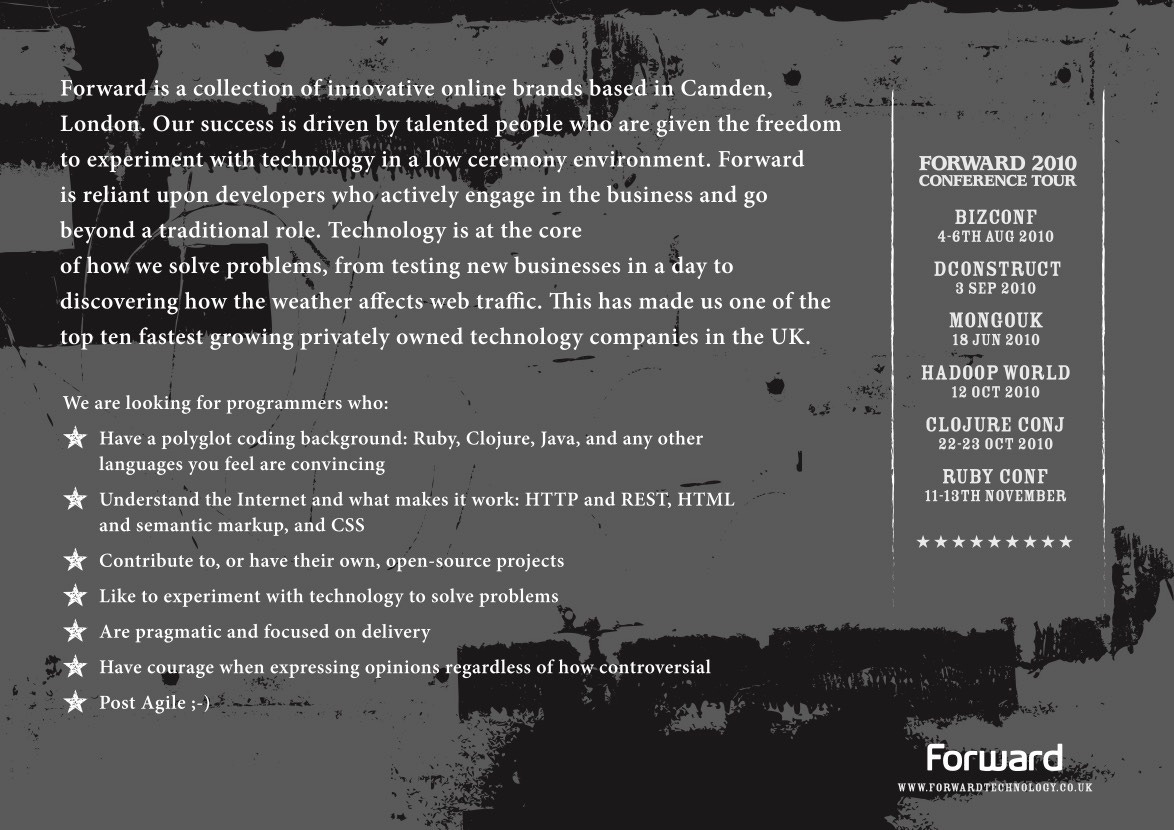

The Confident Exit

After leaving the consultancy, I helped build a new organisation. We were lean, fast, and proudly “post-Agile.” We even printed flyers with a Fender Twin Amp and a Commodore 64 leaning against it. A not-so-subtle nod to the rockstar developer mythology.

Yeah, I was that guy… but for a working-class kid from the north of England, this was as close as I’d get to being Kurt Cobain or Eddie Vedder. I’d given up on drums, so a rockstar developer would have to do.

Post-Agile meant stripping away process and structure. Small teams hacking on code, using everything we’d learned to ship fast, adopting any tool that didn’t slow us down. It was awesome, at least for a while. We shipped quickly, decided faster, and achieved success that almost vindicated leaving the ceremony behind. Look at us, thriving without all those awkward rituals.

What we didn’t see was that we weren’t post-Agile at all. We were products of Agile. The practices we’d dismissed had already shaped how we thought, communicated, and worked, giving us instincts we didn’t even realise we’d developed whilst standing awkwardly with that conch in our hands.

We’d thrown away the ladder after we’d climbed it.

The Humbling

Over the next few years, the business scaled quickly. We acquired a much larger organisation. Suddenly, we had parallel teams, complex dependencies, and people who hadn’t lived through the same formative experiences.

One leader we worked with named it: “developer anarchy.” One of his friends, some industry luminary, visited us, trying to figure out how we were shipping without unit tests. (We just did functional tests. Faster that way.) We took it as validation. Look at us, breaking all the rules and making it work.

Except it wasn’t working. Not anymore. The edges were straining, it wasn’t scaling, and a small group of us were doing way too much to hold everything together. Personally, I was working until 2am every night, rewriting what teams had done, trying to hold it together through sheer force of will.

Two of my colleagues sat me down at a bank of desks in Camden, right next to this huge keyhole door inspired by Alice in Wonderland. Surrounded by all that opulent confirmation bias (our cool office, our rockstar mythology), they told me the truth.

“Mike, this isn’t working. We need to start doing standard Agile stuff again.”

They were right. The ride was over. I couldn’t keep rewriting everything each night.

The practices I’d mocked were actually artefacts of an environment that created the conditions for learning, for better instincts to form. Once I’d learned the lessons, I’d mistaken the outcome for proof that the process was unnecessary.

So we went back to basics. Implemented all the XP and Agile practices: stand-ups, structured planning, showcases, pairing, and TDD. Just in time.

The Invisible Classroom

I didn’t understand what that environment had done for me until I became responsible for creating one.

The practices weren’t about the rituals themselves.

Those early years at the consultancy, hours sitting next to the smartest people I’d ever worked with, people who’d literally written the books on XP and Agile and the frameworks we used, that was where I actually learned my craft. Not just from writing code, but from watching how they worked, seeing their habits first-hand, absorbing the thousand small decisions that separate effective developers from merely productive ones. I learned to master the tools we used because if you didn’t, you had to put a pound in the jar (which is why it still pisses me off when people don’t use shortcuts, even in Google Docs).

They were exploring better ways to work and learn together: to pair programme, to articulate your thinking, to defend your position, to see how someone else approached a problem, to get immediate feedback when you did something inefficiently.

I thought the only value was in the code we shipped. I missed the value of learning from people who knew what good looked like, especially when you’re early in your career and don’t yet know what you don’t know.

The Pattern Repeats

Lately, I keep seeing the “post-Agile” attitude surface on social media, often from developers who’ve never experienced what those practices were actually trying to solve. Worse, remote work and AI mean people can look productive without ever being in the room. No proximity, no real-time feedback, no having to hold the conch and explain your thinking to someone who’ll spot the flaw in your logic before you waste a day implementing it.

Those practices (TDD, pairing, continuous integration, fast feedback loops) weren’t just about producing code. They were about building instincts, learning to see what’s wrong before it becomes a problem, developing the muscle memory that makes you effective over a career, not just in the moment.

You can’t shortcut the acquisition of these skills, especially early in your career when you’re still forming the habits that will define how you work for decades. It requires hours of making mistakes and getting corrected in real time by someone who knows better, someone who can show you not just what to fix but how to think about preventing the problem next time. But now people can produce code without ever seeing how someone experienced thinks through a problem, without anyone sitting next to them, correcting bad habits as they form.

There’s a Japanese martial arts concept that describes this progression. Shu Ha Ri. (Yeah, I learned about that there, too.) Shu is following the rules. Ha is breaking from the form once you’ve mastered it. Ri is transcendence: moving freely because the principles are internalised.

AI and remote work let people jump straight to what looks like Ri, bypassing the years of Shu where you build the foundational understanding that makes breaking the rules productive rather than chaotic. But without mastering the fundamentals first, you’re just mimicking transcendence. You look productive, but you haven’t built the instincts that make you effective.

The Message I’d Send Back

A few years back, a former colleague messaged me on LinkedIn. They’d reached a similar level of seniority and wanted to thank me for the environment I’d helped create. They finally understood how hard it was to do something like that.

That message stuck with me. Not just because it was kind, but because it disturbed me. It reflected my own failure to complete the same journey. I’d understood the impact they’d had on me, but I’d never acknowledged it.

So my penance is writing the postcard my 20-something self needed. The one reminding him to embrace Shu, not skip it. Wax on, wax off.

Recognise the privilege of learning from people ahead of you. Show some humility and let them shape you. It matters more than you think, particularly when you’re still figuring out what good looks like. You’re surrounded by them now but these opportunities get rarer, and you’ll wish you’d made the most of them.

Value being in the room. You learn faster when you can ask why. The learning happens at the whiteboard, in the pauses, in the way someone structures their thinking. In the immediate correction when you’re about to make a mistake. Absorb as much as you can when you’re together so you’re effective when you’re on your own.

Try new things. Lean into the awkward. You’ll get more from those weird practices than you think. Some will land, some won’t, but you’ll take something from all of them. Stay critical, just not cynical. Just keep off the Kool-Aid or you’ll end up in a toe-curling Agile music video.

It took me 20 years to see this clearly. Even now, I know I’m missing what’s shaping me.

In another 20 years, I suspect I’ll wish I’d understood we needed to act now. To deliberately create environments where these lessons can be learned, even as the world retreats from presence and embraces AI assistance.

That’s the next postcard I’ll be writing, just not on the back of a Fender Twin Amp.